Painstakingly, snippet by snippet, the parents of former NFL and Stanford football player Stanley Tobias Wilson Jr. collect information about the last day of their son’s life.

It’s agonizing work. Wilson had been locked up for more than five months at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in downtown Los Angeles after he’d entered a home in the Hollywood Hills during a psychotic break. On Feb. 1, 2023, he was transported by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies to Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk for psychiatric treatment.

He arrived at 9:50 that morning, and 37 minutes later he was pronounced dead. He was 40 years old.

Precisely where did he die? Precisely how did he die? And why, his parents ask, were they given conflicting accounts of his death? It’s been a year and they still don’t have answers.

Under the federal Death in Custody Reporting Act and a California law that took effect last January, when a person dies while in custody the agency with jurisdiction over the correctional facility must post information online within 10 days, including the “manner and means of death.”

No such information has been posted about Wilson because neither the Sheriff’s Department nor the Department of State Hospitals has assumed “custodial responsibility.” In other words, both agencies contend he was in the custody of the other when he died.

Exasperated by their search for answers, Wilson’s parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Department, the Department of State Hospitals and L.A. County in September, seeking $45 million.

“They didn’t count a person who was a Stanford graduate and an NFL player, so they must not be counting somebody dying in custody who was homeless, somebody estranged from their family, somebody they might think isn’t worthy of being counted,” said Wilson’s mother, Pulane Lucas. “I hope his circumstances can shed light on all the others who are uncounted.”

Pulane Lucas, with Stanley Wilson Jr. as a boy, says he often told her, “Mom, it’s a new day, there are new possibilities. Remember, Mom, to make space for miracles.”

(Family of Stanley Wilson Jr.)

Other questions about Wilson — about his life and actions — also remain. How did a man with a decorated past and promising future go off the rails? What led to his incarceration? And did blows to the head received while playing football contribute?

Wilson’s family may never know. But his descent into drug use, mental illness and crime is sadly familiar to them. His father, Stanley Wilson Sr., also played in the NFL but is known primarily for missing Super Bowl XXIII in 1989 after binging on crack cocaine the night before the game.

The Wilson family saga is of a father and son who shared tremendous athletic prowess, but faced monstrous personal demons.

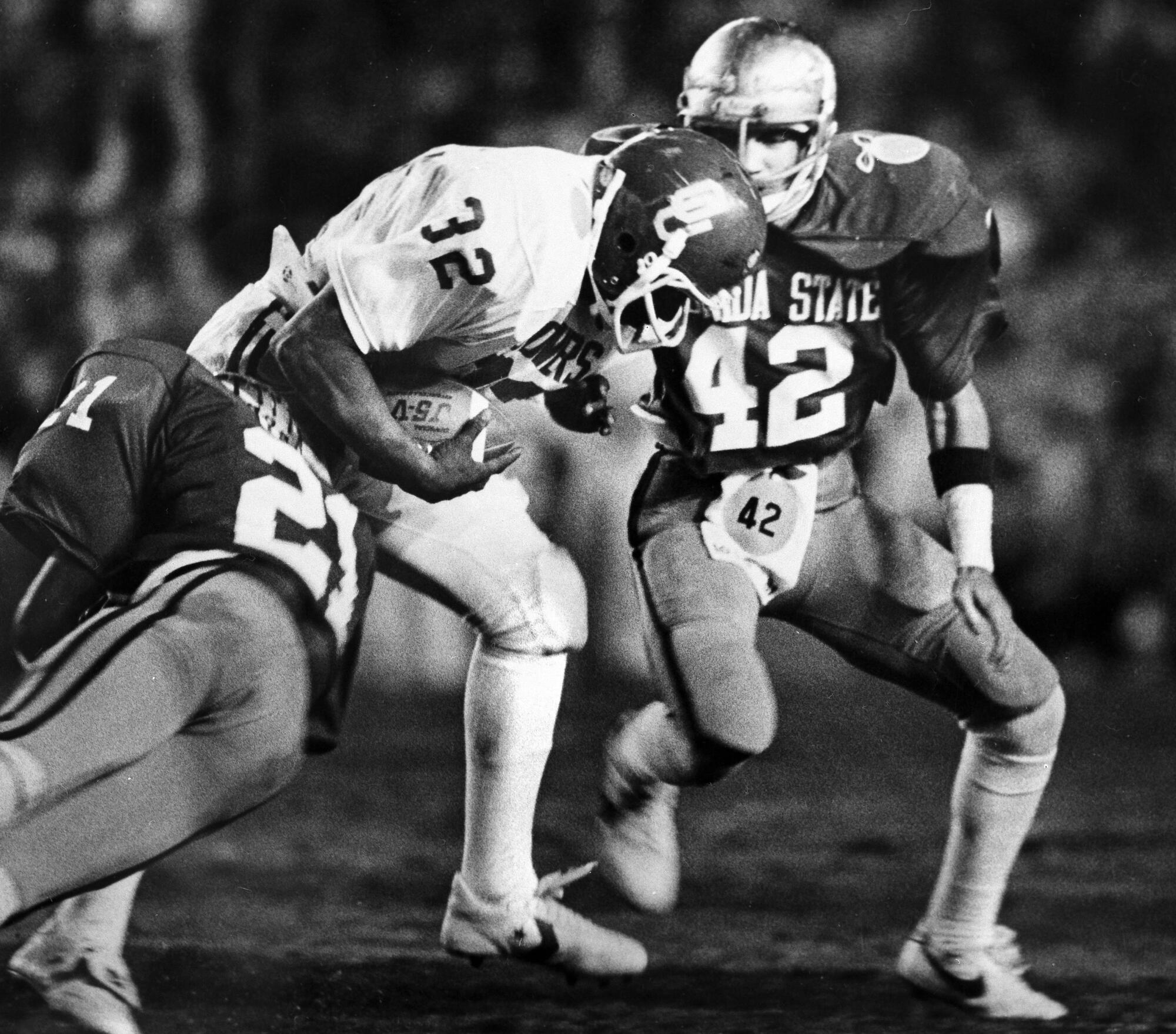

Stanley Wilson Sr. (32) played football for the University of Oklahoma in college. Here he carries the ball against Florida State during the 1981 Orange Bowl in Miami.

(Associated Press)

Stanley Jr. was born Nov. 5, 1982. His parents were students at the University of Oklahoma, and the next day Stanley Sr. rushed for 143 yards in the Sooners’ 24-10 victory over Kansas State.

A few years earlier, he had been the L.A. City Section player of the year at Wilmington Banning High. At Oklahoma, he flourished — rushing for more than 1,000 yards in 1981. But college was also where he first tried cocaine.

The Cincinnati Bengals realized their rookie running back had an addiction problem soon after drafting him in 1983. They sent him to three rehab centers, but he relapsed in August 1984 and was suspended through the 1985 season. He played well in 1986 but was suspended a second time for the 1987 season.

The Bengals stuck with him, and he was key to the team’s 1988 run to the Super Bowl. Wilson Sr. hadn’t failed a drug test all season, but when a few teammates mentioned scoring some cocaine in the days before the game in Miami in January 1989, he couldn’t resist.

He smoked and snorted a large amount of cocaine and missed a team meeting the night before the game, and an assistant coach found him sitting in the bathroom of his hotel room in a cold sweat. Coach Sam Wyche cried while informing the team, and without Wilson the Bengals lost, 20-16, to the San Francisco 49ers.

Stanley Wilson Jr. moved back to California to live with his grandparents, Beverly and Henry Wilson, by the time he was in elementary school.

(Family of Stanley Wilson Jr.)

Wilson Sr. had paid for his parents and 6-year-old son to fly from L.A. to Miami. He even rented a limousine to take them to the game. Wilson’s grandparents broke the news that his father wouldn’t be playing after all.

“My grandparents told me my father had gotten in trouble, and they asked me if I still wanted to go to the game,” Wilson told The Times in 2005. “I didn’t understand what was going on, and I told them I did. We went, and it was awkward. It was surreal.”

As a toddler, he had lived with his parents in Cincinnati until his father’s drug use led to a breakup. Wilson and his mother moved to Lucas’ hometown of Oakland, then to Cambridge, Mass., where he was a ballboy for the Harvard men’s basketball team while his mom pursued advanced degrees. She would earn three master’s degrees from Harvard. Lucas also received a Ph.D. in public policy and administration from Virginia Commonwealth University.

At age 6, Wilson returned to Southern California to live with his grandparents, Henry and Beverly Wilson, in the same house in Carson where his father grew up.

“He needed male role models, and I thought he’d be better off in a two-parent Christian home,” Lucas said.

At 12, Wilson told his mom he wanted to change his first name to Darren because whenever the Super Bowl rolled around, he was reminded of his father’s failings. “Every year he’d see something like the top-10 Super Bowl meltdowns, and kids at school could be mean,” Lucas said.

Wilson Sr. was mostly absent from his son’s life but surfaced as a volunteer assistant coach on his son’s 8-man football team in 1996, when Wilson was a high school freshman. Father and son were happy to spend time together, and Wilson Sr. had a chance to recount his own playing days, telling The Times back then, “That’s what is so neat about this, that I can sit down with him and go over my old videotapes and say, ‘Look, Stan, that’s your dad.’”

Wilson Sr. was struggling with long-term addiction, he openly says now, and suffered from psychotic episodes stemming from bipolar 1 disorder. He had turned to crime to feed his cocaine habit and, two years after reentering his son’s life, was sentenced to 17 years in state prison for burglarizing a Beverly Hills mansion, his third such arrest.

Stanley Wilson Sr. wipes a tear during his sentencing at a Los Angeles court room in 1999.

(Reed Saxon / Associated Press)

A sophomore at Bishop Montgomery High in Torrance, Wilson would visit his father at the prison in Lancaster and eventually became a mentor in a child visitation program, where he counseled others with incarcerated parents.

“He had a relationship with his father and I was happy about that,” Lucas said. “He was an African American young man, and I really wanted that for him. I wanted him to be in his grandfather’s presence as well.”

The boy once ashamed to be known as Stanley Wilson no longer wished to change his name.

“I think right about that time he really moved forward into football,” Lucas said. “I think his goal was to bring honor to the name Stanley T. Wilson.”

That certainly was the case in 2005 when Wilson Sr. was six years into his sentence and Wilson was on the cusp of being drafted as a cornerback by the Detroit Lions.

“I’m happy to represent my dad,” Wilson Jr. told the Dallas Morning News that year. “It’s a blessing and a tribute to him that I’m here. A lot of people who might have a past like I do could have fallen by the wayside. The fact that I’m here today shows he’s a great dad.”

Detroit Lions cornerback Stanley Wilson Jr., right, celebrates with cornerback Keith Smith after Smith returned an interception 64 yards for a touchdown against the Chicago Bears on Sept. 30, 2007.

(Duane Burleson / Associated Press)

After playing at Stanford, Wilson was drafted by the Detroit Lions but lasted just three seasons. An Achilles tendon injury during the 2008 preseason forced his retirement.

Wilson, who had earned a bachelor’s in urban studies from Stanford, completed the NFL Business Management and Entrepreneurial Program at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania But over the next few years, Wilson drifted.

He considered becoming a doctor, then got a bachelor’s degree in nursing at Hunter College in New York. Like his father, Lucas said, he developed a drug addiction and began showing signs of bipolar disorder.

After his death, Wilson’s brain was found to show signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the debilitating disorder common among football players and caused by repeated head trauma.

Lucas said she first became aware of her son’s deteriorating mental health in 2014, when a couple called her from New York City and said, “Your son gave me your phone number. We saw him walking down the street naked, but he was clean cut so we knew something was wrong. We took him to a hotel and paid for a room and we want you to know he’s OK.”

Stripping naked in public is occasionally a feature of bipolar 1 manic episodes, according to psychiatrists.

Wilson moved to Portland, Ore., and in June 2016 was arrested for climbing through a window into a mansion while naked — prompting the terrified 78-year-old homeowner to shoot him in the abdomen. When police arrived, Wilson was standing in a backyard water fountain cupping his wound.

He pleaded no contest to trespassing charges and to felony first-degree burglary for entering another home earlier that same day, making himself a drink and taking a book. Court records indicate Wilson also walked into or lurked in the yards of two other homes in the same upscale neighborhood while naked.

He was sentenced to 10 days in jail after telling the judge he was “happy to be alive.”

Lucas, who was living in Virginia, had near daily contact with Wilson by phone or text. She said that’s when he revealed that he’d been molested as a child by a male babysitter.

“I asked him, why are you going into these people’s homes? I don’t get it,” she said. “And he said, ‘I have to save the children from [molestation].’ Then I asked him, what is this, taking your clothes off and getting in these people’s fountains? He told me, ‘Mom, I have to cleanse my soul from what was done to me so that if I die I’ll go to heaven.”